Minna Dubin: On not wanting to be ‘just Mom’ and dealing with the critics

Advice from the author of ’Mom Rage’

Meet our next creator, Minna Dubin:

Minna Dubin

Age: 42

Children: Boy, 10; Girl, 6

Vocation: Writer

Location: Berkeley, CA

Links: Minna Dubin, #MomLists

You have probably come across Minna Dubin’s New York Times’ essay on mom rage. It first ran in 2019 but was republished in April 2020, a month into the woman-crushing failed social experiment of lockdown. The essay went viral for saying the things we don’t say and admitting to the things we don’t admit, even to ourselves—that motherhood can push us to the point of madness, and we sometimes take it out on our children.

It’s a continuation of Anne Lamott’s 1998 essay in Salon, titled “Mother rage: theory and practice.” Two very similar essays, 20 years apart. That doesn’t make society’s evolution look very good.

Both essays acknowledge that those of us who have a tendency to rage are not mad at the thing we’re raging at—at the spilled cup of milk, say. Rather, we’re raging at the 10, 20, 100 things—the partner who won’t prioritize family, the crushing bills for childcare, the boss who doesn’t understand that children get sick, etc., ad infinitum—that happened before that moment. We stay calm until we don’t, and then we snap and are literally crying over spilled milk.

Minna has turned that essay into a book, Mom Rage: The Everyday Crisis of Modern Motherhood. In the book, she delves much deeper into the cultural, societal, patriarchal reasons why mothers might be cowed by rage. It’s a very personal book about her journey as a mother of two, one of which is neurodivergent, offering his own unique set of parenting challenges. Her honesty is refreshing, and it’s ultimately a book that inspires hope.

Before I chatted with Minna, I was expecting to talk a lot about how children trigger rage in us. But my big takeaway, instead, was how motherhood can be a wonderful trigger for motivation in creative moms. For Minna, it was the fear of losing her identity, losing her aspirations and being swallowed up by Motherhood, that lit the fire under her to get serious about her art.

There’s the saying, “If you want something done, ask a busy person.” A recurring theme from the women I talk to is how much more efficient they are once they become mothers. They have limited time, and they take full advantage of whatever time they can wrestle away for themselves because they now understand how precious it is.

But motherhood, especially early motherhood, is also a moment when you understand mortality and time in a more visceral way than ever before. You’ve just created your replacement. You’re raising the person who will take up your space on this planet. You watch your time tick down with each inch they grow. You stand as a barrier between them and death, allowing their youthful sense of immortality, just as you watch your own previously taken-for-granted wall between here and the hereafter crack and fall.

It can be easy, as Minna says, to go all in on Momming and to Mom the hell out of the job. For some women, that is what they’re meant to do, and that is fantastic. But if it’s not your dream, you’re just putting a bandaid over the void, and when that bandaid is ripped off—which the children will do for us, all too soon, way before we think it’s time—that gaping wound will still be there. And it can only be filled by our artistic creations.

So if we’re going to rage, let it be in Dylan Thomas’s vein. Let us rage because we haven’t accomplished enough. Let us rage with the fire to get done what we’ve always wanted to get done, so we don’t have to rage in our final days for a lack of trying. And may we stop raging because our kid won’t put on their damn shoes.

Easier said than done, of course. But let us also follow Anne Lamott’s guidance:

“Good therapy helps. Good friends help. Pretending that we are doing better than we are doesn’t. Shame doesn’t. Being heard does.”

So let’s hear from Minna, in her own words…

On refusing to be “just Mom”:

Becoming a mother put a serious fire under me creatively. I felt a lot of pressure, or a lot of fear, actually, that I was just Mom, and the whole world saw me as just Mom. And it would have been so easy to slide into being just Mom. Nobody would have stopped me. So I think that that scared me enough that I got very serious about writing because I saw the alternative was so eagerly waiting for me to just be a mom. Not that there’s anything wrong with that being your job if that’s your calling, but it was not mine.

I would have felt very unfulfilled to be just Mom. I always wanted to be a writer and have always been writing. But I was never doing it so intensively, or toward major professional goals. You know, I might publish an essay here or there. It was very lackadaisical, my writing. And once I had kids, and I realized that I could lose it, I could let it go so easily, it made me get very serious about it.

On dealing with criticism:

Every once in a while, I’ll get an email or message on one of the socials that will say something like, “You’re mentally ill,” basically. Those few emails I get, they’re not great to get, but I just delete them. And for every email that I get that’s nasty, I get 100 that are grateful and thankful from mothers who reach out. Also, mothers who speak out against the tiny box of what mothers are supposed to be, and anyone who speaks out against the way that patriarchy oppresses women, and particularly mothers, get punished. Angry women and angry mothers are always called mentally ill, abusive, neglectful. It’s a way to silence mothers.

I read that New Yorker article. [Editor’s note: The New Yorker ran a less-than-kind piece on Mom Rage.] I think that women can help serve the patriarchy. Women can be part of the oppression of other women. But basically, I just sort of shrugged.

In a way I was like, wow, I don’t think this is about me. I’m not sure she read my whole book. But also, yay, the New Yorker thought that my book was important enough to give it all of that page space. So I also looked at it like that: this is my first book, and there was a multi-page piece in the New Yorker about it.

But also, if I haven’t pissed people off, I’m probably not saying anything worthwhile.

On mothering ourselves and each other:

Find other mothers who you can talk to about the hard stuff. It was really important when I found a mom who also had a neurodivergent kid who was the same age, also a boy, also navigating the same school system I was navigating, also navigating health insurance. We were on the same road together. So that felt really great.

You need to have moms that you can send that mom-rage text to or the hard text that you write and delete because you don’t know if it’s even appropriate to send to someone and you don’t know how they’re going to feel about you if you say this thing. You need to be able to say the thing and have people who won’t judge you and who are going to send you the same kind of texts back so that you can mother them back.

So much of it feels like we have to mother ourselves in motherhood. To have some mom friends who you can mother each other in that way can be really healing and helpful in making things feel less dire when they feel bad. And also make you laugh. You know, because none of it is actually that huge of a deal. But there are moments where you get so overwhelmed.

On keeping the creative momentum going:

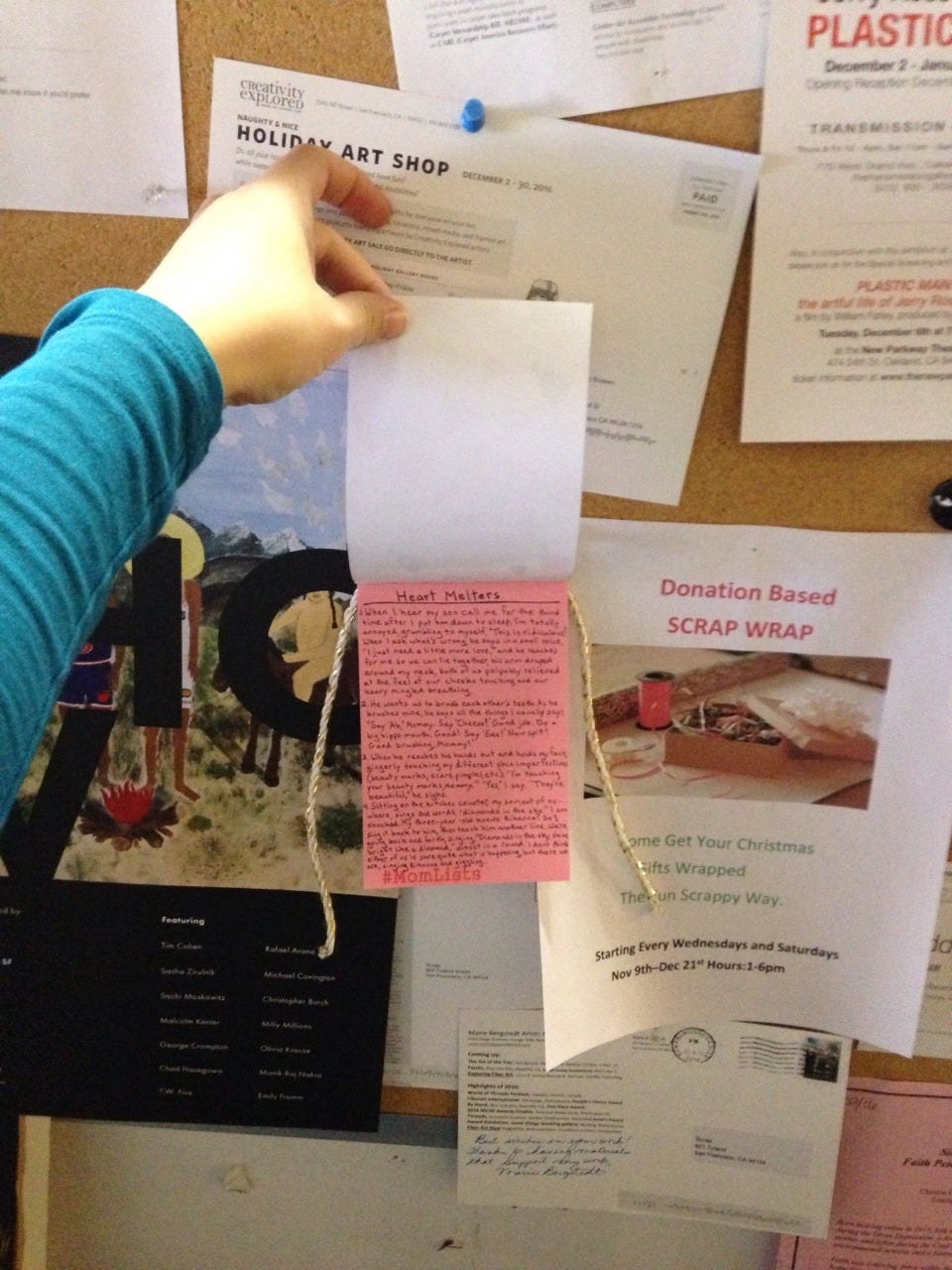

When I think about the creative process, it always feels important to encourage writers and artists to keep making things because each thing or each project leads to the next project. We never know the importance for our careers of what we’re making. Like, this book came from that essay. And that essay came from another book that never got published that came from a three-year public art project I did where I wrote these wacky lists [#MomLists] about motherhood and posted them all over the Bay Area. And one of those lists was about mom rage.

I did that project for three years in order to get myself to start writing again after I became a mother. So each thing we do artistically leads to the next thing we do. And we never know the trajectory of it. But it’s all moving forward toward something better. And sometimes it’s just at a different speed than other times.

Thank you for sharing, Minna!

*Interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Personally, I LOVED this interview and I am going to check out her new book. Women can have not only a creative renaissance after they have a child, they can also start asking themselves WHO they were BEFORE that child came along. I have found that when I ask myself what I want, and care less about what my children are up to, I alleviate some of the stress and tediousness around the every day. If I have my eye on a larger goal for myself, that purpose / meaning / direction for my nervous energy – creates a kind of inner calm. I will also be less affected by a tantrum, take it less personally, not react as if my world was crumbling alongside of theirs. Having a project or some creative outlet to chip away at every day, gives me confidence, and I can respond much better to stress when I have a boost from doing something nice for myself. I feel a new Substack post coming on! Thank you for this wonderful and honest content!

I love these interviews for the most part, but today’s is disturbing to me. I worry that normalizing “rage” as a society creates more harm than good. I began reading this book as I can relate to these moments of anger, a feeling of not being a good mother, and losing my cool. After the first chapter, I had to stop reading this book because it was frankly too upsetting. The author describes her kid hitting his head on the ground, “maybe I pushed too hard” (MAYBE?). This loss of control in the author’s behavior should not be considered typical or okay. There is no “maybe” here, and the refusal to take responsibility for causing one’s child physical harm was upsetting. AS MOTHERS, we are responsible for our actions despite externalities that put pressure on us.

As parents, we are stewards of unique and beautiful and, yes, sometimes difficult children who look to us for safety. The long-lasting impacts of childhood trauma affect not just our children’s health but society’s health as a whole. While I appreciate this interview’s insight on creativity and motherhood, I am concerned about normalizing rage toward anyone, particularly rage towards children. If anyone feels this type of rage, please reach out to any support network you have, such as friends, partners, neighbors, other parents, therapists, and psychiatrists.