Rose Marie Cromwell: On photographing through postpartum, traveling for work, and living a 'wide' life

Advice from a photo and video artist

Meet our next creator, Rose Marie Cromwell:

Rose Marie Cromwell

Age: 39

Child: Simone, 3

Location: Miami

Profession: Photo and video artist

Website: Rose Marie Cromwell

Rose is a photo and video artist with a diverse practice. She’s worked for The New York Times, The New Yorker, and National Geographic. She partners with brands for promotional photography, and she’s published three books and is working on a fourth.

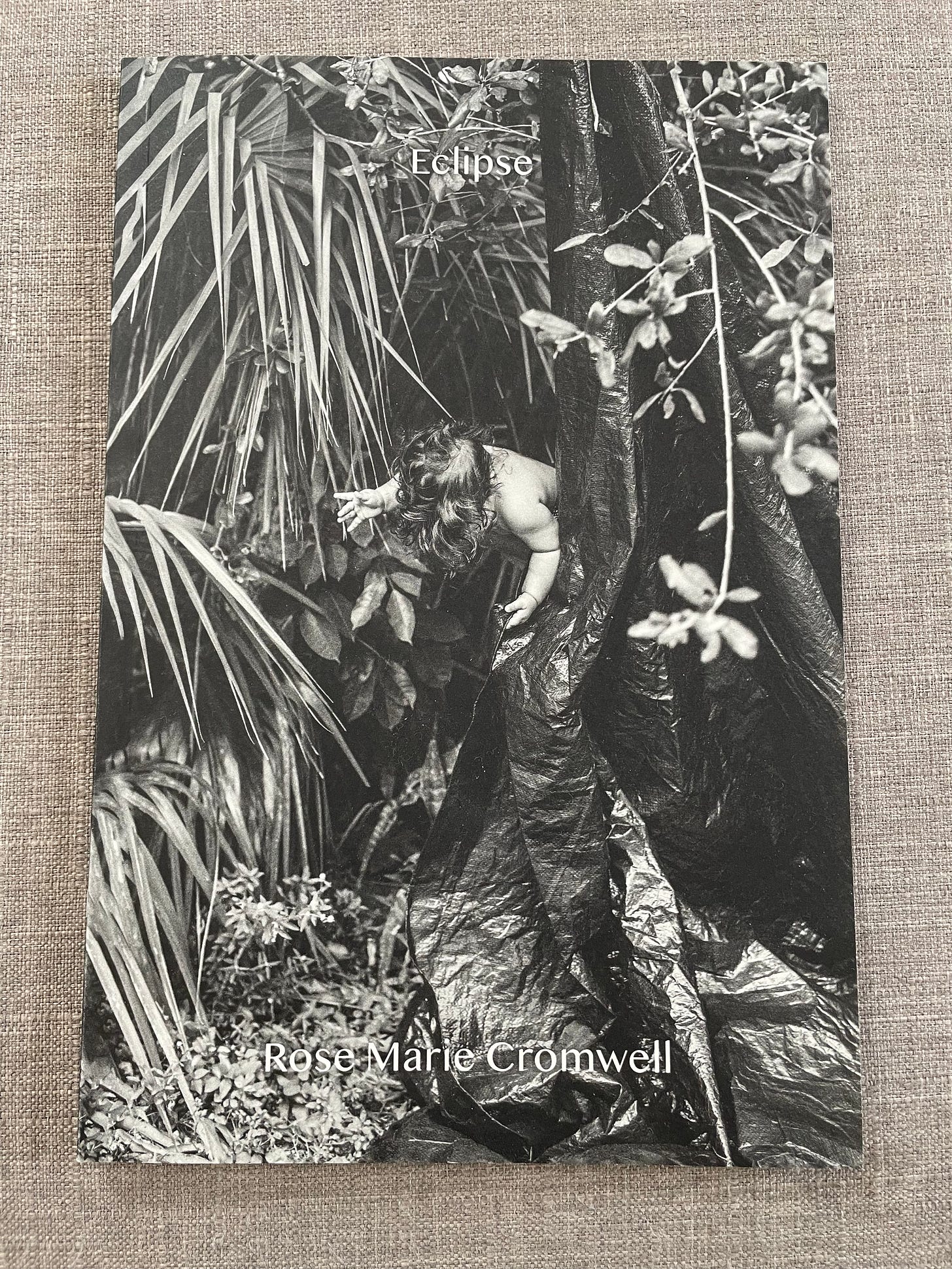

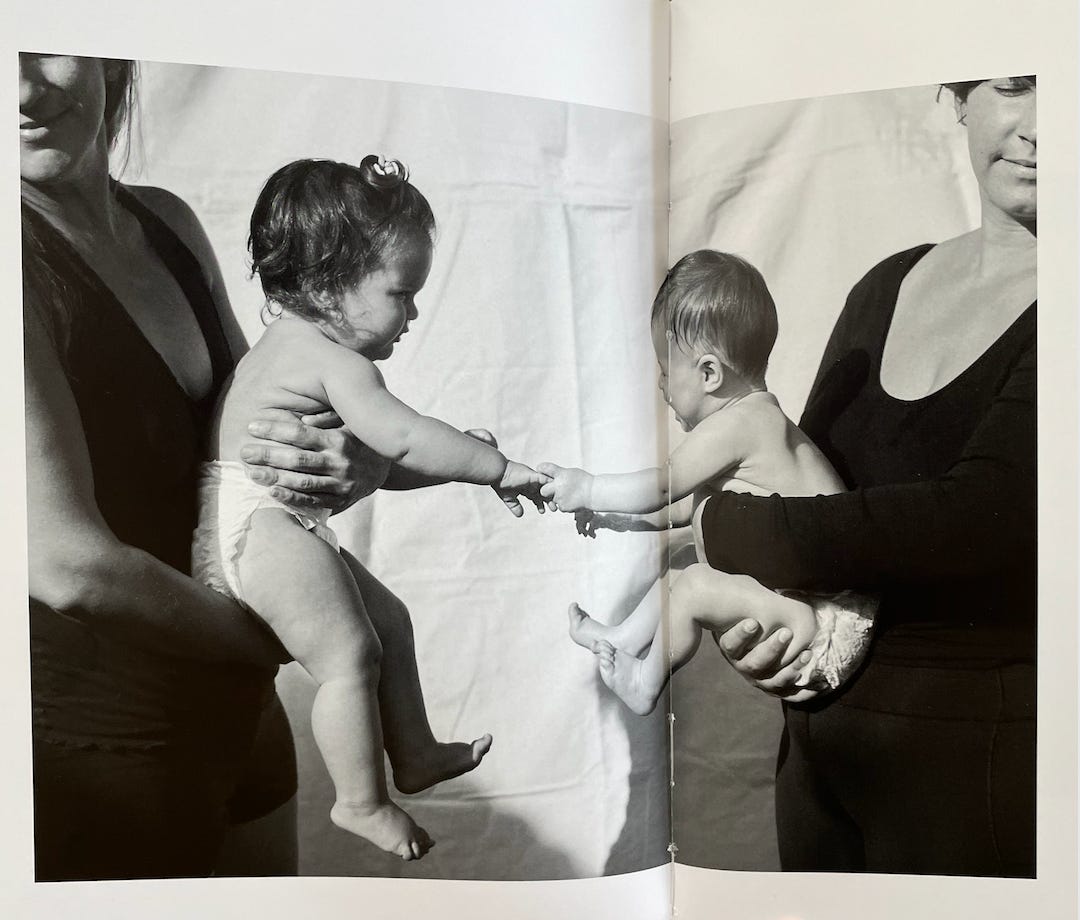

Chatting with Rose brought up memories and feelings that I, probably out of self-preservation, haven’t revisited in some time. One of the photography books she published is called Eclipse, and it’s a beautiful, honest portrait of the postpartum era.

Every woman’s birthing experience is unique and traumatic despite its utter and shocking normalcy. Normal because the majority of women experience childbirth, and obviously every human being is a result of it. And yet, when it’s happening, it seems an impossibility. It seems like, surely, this is not how it’s supposed to go.

Every woman who’s had a child knows that there is little in life that brings you closer to death than giving birth. And I don’t mean simply life-threatening labors. But you just become very aware of the reality of death, and you sense its nearness during the process. You sense it when a complete helplessness washes over you when the contractions tip beyond the point of knowable pain, and you realize that there is only one direction to go. There’s no going back, there’s no opting out, and it’s a deeply disturbing realization, one that I can only imagine mimics what it feels like to be terminal and know your time is almost up. Or you sense it when the pain becomes all-encompassing, and your consciousness turns inside out, burrowing deep down into a private world you didn’t know you had, to a place where you bear and endure, a place that is populated by all the women past and where death lurks, where, when a scalpel slices through your perineum, you barely notice because in this strange place that is equivalent to a paper cut. Or you sense it days later, when you’re sound asleep and you wake with a start because you heard a nothing—the lack of an inhale—you somehow heard when your baby didn’t breath for a few moments, and you instinctively know death is close by.

Giving birth is traumatic, normal and traumatic, and it’s hard not to concentrate on the act itself and then the ensuing creature. What is lost in that focus is that a birth results in two new human beings—because the woman is no longer her former self.

Now I consider myself someone who knows words. My job is to know words. But Rose introduced me to one I’m ashamed I did not know: matrescence. It is the physical, psychological, and emotional changes you go through after the birth of a child. It’s often likened to adolescence, as they both involve hormonal changes, body changes, and the shift in identity and relationships.

When I looked it up in my trusty Merriam-Webster, it was not there, neither in the Collegiate edition nor the New World. I found it only in the online Cambridge dictionary. Every human being should be aware of this word and this concept. If we don’t have words for things, we don’t talk about them, and then they don’t exist. I’m sure this contributes to a lot of the negative emotions many women feel after having a child. Because we don’t know what we’re getting into. We don’t understand how much everything we are and know is about to implode. And if we feel depressed or confused or angry, we think there is something wrong with us instead of knowing and embracing that we are entering a new phase of life. You don’t look the same, you don’t think the same, you don’t feel the same. You have been down into the pit and felt death near and come back to walk among us. So let’s talk about it. Let’s normalize it.

Now, Rose Marie Cromwell, in her own words…

On the transition from always moving to not moving:

Right after I had Simone, the pandemic started. So I had a forced maternity leave, which was really great in the long run. While I was pregnant with Simone, I think I went to eight countries. I was probably the most traveled pregnant person I know. I was constantly on the go. My career was really booming at that point, and during the first two weeks of having a baby I had to turn down some really amazing jobs because I just couldn’t physically bring a tiny baby on an airplane. So then the pandemic happened, and it gave me a little bit of peace. And I hate saying that because I know a lot of people suffered during the pandemic. But looking back on it, it was lucky for me that I didn’t have the constant stress of saying no to work after I’d worked so hard to get to that point in my career.

On traveling for work:

It’s liberating, it’s sad, lonely. But what I do, whether I’m with Simone or away from her, is be in the moment and be grateful for where I am. Because if I’m not in the moment, I spend the whole time being sad that we’re apart or feeling like I’m never getting a chance to work or make art. I try not to regret. Those emotions come and go, and I try to deflect them because I made the choice to be where I am; I need to be engaged with whatever I’m doing where I am.

The longest I’ve been away from Simone is two or three weeks. That’s kind of the limit for me at the moment. What makes my lifestyle, my work, possible is a supportive partner. That’s what makes it logistically feasible. He also travels too. So we both spend time alone with Simone.

On processing postpartum through photography:

Giving birth was a kind of jarring, beautiful, scary experience because I had a hemorrhage after I gave birth. It was an out-of-hospital birth of two days, and then I was transferred to the hospital, and I really had to face the existential question of how thin the line is between life and death. But I remember on day 1 ½ of being in labor, my doula asked me what I was afraid of, why I was holding back. And, well, I was afraid of dying. That’s what pain is. That’s what pain signifies to people. Something scary is coming. And she was like, Rose, this is your soulmate. You can’t be afraid of anything. You have to be willing to give it your all. So I imagined myself going down this deep, dark hole looking for Simone and facing my fear of dying and overcoming it.

It was a lot to process afterward. My body was still bleeding a lot. Part of my processing tool was photography. I was photographing the postpartum period. Of how my body looked. Of how tired I looked. Of Simon. Of the pump. The placenta pills, which I think kept me from postpartum depression. All these different things that are so specific to that experience. I was photographing with my iPhone, which is not a tool that I usually would have taken so seriously. But it was the only thing I could manage at that time. I didn’t have the capacity to set up my media format camera.

I was posting those images to a private Instagram account that my publisher who published my first book was following. He said, “We’re thinking of a box set of 12 artists who made work during the pandemic.” I didn’t intend for the photographs to be art necessarily, or to go out into the world more than to just my close circle of friends. But then I realized that maybe they are resonating with people—even with a man who hasn’t had kids, somebody who’s further removed from this process. So I began to make more of a conscious effort, and as both Simone and I stabilized, I could use more complicated cameras and start shooting film and kind of reenacting things. And that became my book called Eclipse.

On motherhood improving artistry:

I used to have this coffee mug that had this quote on it: Life is short, but it’s wide. And for me, motherhood has widened my experience of life. It hasn’t felt limiting in the long view. Yeah, maybe in those first two weeks when I couldn’t do that one job, but in the longer term, it has really been a widening experience for me.

I think that slowing down and making better choices, which are things that need to happen to be a mother and to be an artist, are really beneficial for your art in the long run. It’s helped me be a better artist. It’s helped me be a better working photographer. Because it’s made me more empathetic. I can relate to people better. So I look at motherhood as this benefit rather than hindrance.

Thank you for sharing your story, Rose!

*Interview has been edited for length and clarity.